Unlike architecture and graphic design, service and interaction design haven’t yet discovered a way to exist as both art and as something utilitarian. Sketches by Charles & Ray Eames, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Frank Lloyd Wright hang in museums; those drawings were stages in the design process for products, graphics, and buildings that still serve a practical purpose today.

The way that we sketch our concepts for apps, websites, and services in physical space reflects an emphasis on the utilitarian. In my field, the belief that interactions should be immediately comprehensible and nearly invisible is paramount, and the use of generic patterns is, for many projects, a best practice.

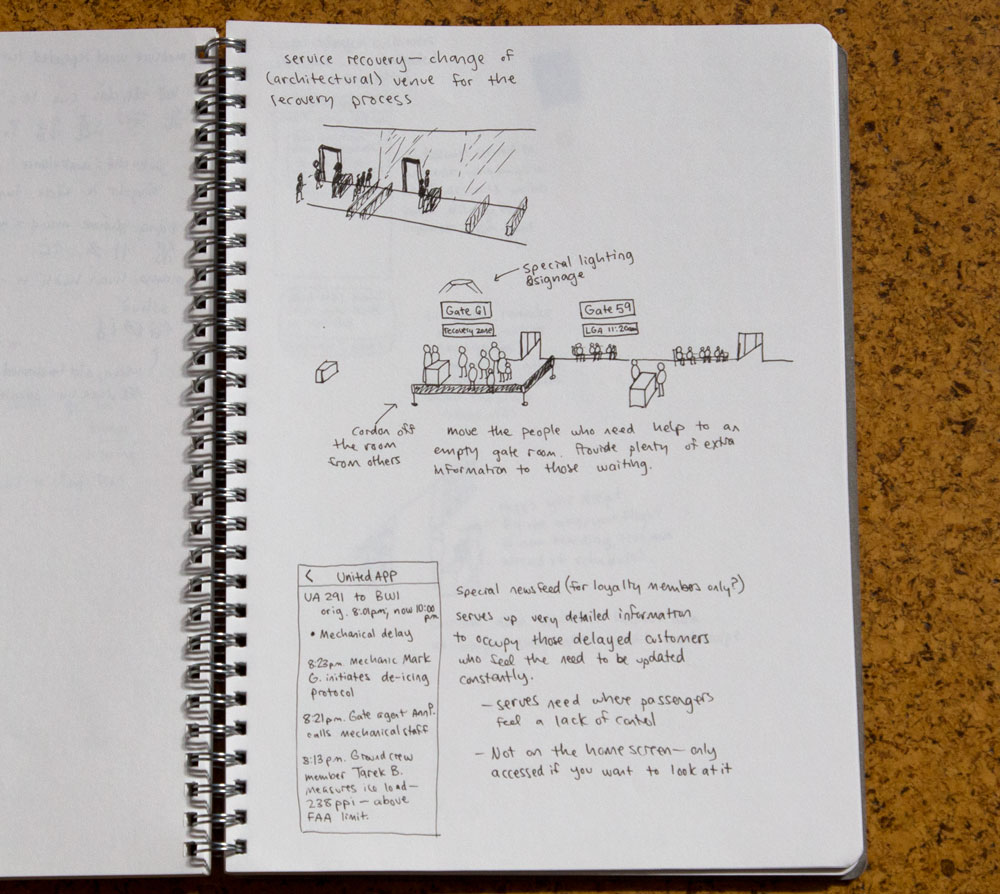

Sketching itself serves a utilitarian purpose for service designers and interaction designers: I use sketching to quickly test out ideas and develop new ideas as I go. Sketching even very common interaction design patterns for smartphone apps (for instance) can reveal new ideas for data visualizations or other interaction features. More often, though, making a quick sketch of an interface that seems simple in your mind can reveal fundamental flaws in the idea.

Sketching intangible services that don’t take place on a screen serves the same purpose. Service designers often like to depict future service designs as stories—primarily text with some illustrations. However, sketching the service in action helps me come up with new ideas for what I’m designing, and can help me realize I’m going down a crazy path.

Service design and interaction design are disciplines that may evolve radically before reaching a level of maturity to where, like architecture, their products can be appreciated in a utilitarian and aesthetic way simultaneously.

This post was published in the December 2015 issue of EG Magazine.